July 21, 2023

CNAS Responds: Oppenheimer and Global Nuclear Security

The much-anticipated release of Oppenheimer has thrust nuclear security back into mainstream discourse. In this edition of CNAS Responds, CNAS experts assess the global state of nuclear security and interrogate the future of humanity’s most powerful weapon and energy source.

All quotes may be used with attribution. To arrange an interview, email Alexa Whaley at [email protected].

Modern Nuclear Threats

Lisa Curtis, Senior Fellow and Director, Indo-Pacific Security Program

Oppenheimer died before the nuclearization of southern Asia, but his witness to three wars in the region—the 1947 Indo-Pakistani war in Kashmir that followed the partition of the Indian subcontinent, the 1962 Sino-Indian conflict, and another Indo-Pakistani war over Kashmir in 1965—would have given him an indication of the dangerous nuclear future that laid in store in this part of the world. Today, China, India, and Pakistan are modernizing nuclear forces and expanding nuclear arsenals, with little hope for any serious dialogue on confidence-building measures to prevent the use of nuclear weapons, which would be devastating for a region that contains 40 percent of the world’s population.

As NSC Senior Director for South and Central Asia from 2017 to 2021, I dealt first-hand with two major crises in southern Asia. The first was in February 2019 following a major terrorist attack against Indian security forces in Kashmir. That led to an Indian retaliatory strike against an alleged terrorist training camp deep inside Pakistani territory and an ensuing dogfight between Pakistani and Indian fighter jets. Thankfully, both sides took an early opportunity to de-escalate the military crisis, but things could have gone in a different, potentially catastrophic, direction between the nuclear-armed foes.

One year later in the spring of 2020, when the world was distracted by the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, fighting broke out between Indian and Chinese forces along their disputed border in Ladakh, leading to the first loss of life along the India-China border in 45 years. This situation has also since abated, but both India and China retain high numbers of troops along their disputed frontier, and another military crisis could erupt at any moment. In March, CNAS published a paper, “India-China Border Tensions and U.S. Strategy in the Indo-Pacific,” arguing for U.S. policymakers to focus more attention on the risks of a future India-China conflict and to consider more carefully how best to prevent one from occurring.

Oppenheimer is likely to provide thrilling entertainment to moviegoers. It should also serve as a reminder to U.S. policymakers to renew their focus on nuclear competition in southern Asia and to redouble efforts to reduce the potential for future conflict in this increasingly nuclearized region.

Dr. Duyeon Kim, Adjunct Senior Fellow, Indo-Pacific Security Program

Oppenheimer is a very timely, important reminder about the dangers and catastrophic effects of nuclear weapons at a time when nuclear risks are now higher with multiple nuclear competitors and aggressive nuclear-armed states. Putin threatened to use tactical nuclear weapons after Russia waged an illegal and unprovoked war in Ukraine. Kim Jong Un continues to fire ballistic missiles and lodge implicit threats to use nuclear weapons—he could use nuclear weapons first based on misperception or false warning because his nuclear doctrine allows North Korea to launch a nuclear strike “automatically and immediately.” China, which the U.S. Defense Department calls the “pacing challenge,” continues to modernize and expand its nuclear weapons program with more types and numbers. Both nuclear deterrence and integrated deterrence have become more important than ever, making diplomacy even more critical to reduce risk and prevent nuclear catastrophe from miscalculation, misperception and escalation. While Washington understandably has its plate full with more urgent issues regarding China and Russia, failing to make progress and find eventual solutions to the North Korean nuclear problem could lead to even bigger challenges in Northeast Asia and the Middle East.

Nicholas Lokker, Research Associate, Transatlantic Security Program

Russia’s aggressive nuclear posturing following its 2022 invasion of Ukraine has brought the specter of nuclear war to the forefront of international attention. By adopting increasingly permissive and unreliable nuclear rhetoric, as well as by deciding to suspend participation in New START and station nonstrategic nuclear weapons in Belarus, Moscow has demonstrated a heightened reliance on nuclear coercion as a tool of foreign and security policy. This reliance is likely to persist as long as current trends hold, with an economically constrained Russia attempting to offset the degradation of its conventional military forces while facing a strengthened NATO.

Going forward, it is reasonable to expect that Russia will look for opportunities to increase the credibility of its nuclear threats by bolstering its nuclear force posture. Moscow is also likely to attempt to use nuclear weapons to test NATO’s cohesion and demonstrate its own enduring great-power status. The United States and its allies must prepare now for the various potential implications of the evolving Russian nuclear threat, including reduced opportunities for nuclear arms control, changing views about acceptable nuclear use among the Russian public, and greater risks of unintended escalation resulting in a shortened pathway to nuclear war.

Arona Baigal, Research Assistant, Middle East Security Program & Securing U.S. Democracy Initiative

As we’re all eagerly anticipating watching Oppenheimer, we should take a step back and look at why we are deeply intrigued with J. Robert Oppenheimer himself, not just the Manhattan Project backstory. As with many aspects of foreign policy and international crises, the strong personalities of political actors matter. We see this in the discourse of what it means to be a rational actor, the nature of authoritarian leaders, etc.

In the context of nuclear weapons and nuclear security, we see how personalities, history, and political culture influence nuclear decision-making. For example, in Iran’s nuclear decision-making, the regime’s leadership’s security decision-making is through the lens of feeling like they have been backed into a corner. In other words, Iranian leaders view a nuclear weapon as a means of self-preservation. The themes we will most likely see from the film will make us reflect on how far leaders will go for self-preservation, conceptualizing what it means to have mutually assured destruction. These strong personalities in global political and security leadership will negatively impact strong nonproliferation policies.

Rebecca Wittner, Intern, Indo-Pacific Security Program

At a time of heightened geopolitical tensions and a struggle to uphold a rules-based international order, the United States' focus on Indo-Pacific security is important in working to mitigate the threat from nuclear states such as China and North Korea. The recent port call in South Korea of a U.S. Ohio-class nuclear-capable submarine demonstrates the United States' commitment to nuclear security not just regionally, but worldwide. Moreover, developments in the U.S.-ROK alliance such as the Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) signal a clear progression towards working closely alongside allies and partners to further common objectives. The NCG inaugural meeting—which occurred this week—reaffirmed the role that America and South Korea seek in bolstering deterrence in the Indo-Pacific, which is critical at the juncture of both nuclear and international security.

American Nuclear Power in the 2020s

Katherine Kuzminski, Senior Fellow and Director, Military, Veterans, and Society Program

The fundamental driver of nuclear advancements and security is human capital. With the potential for private sector growth in the nuclear energy field, the U.S. government must invest in the development and retention of highly technically skilled nuclear talent within the national lab system. The federal government should place a particular emphasis on recruiting and retaining recent nuclear physics PhDs; only 16 percent of recent graduates with the requisite training are employed by the federal government, while the majority (57 percent) join the private sector. The federal government must further cultivate a cadre of human capital dedicated to understanding the policy and issues of national concern regarding the generation and use of nuclear power.

Ayla McBreen, Intern, Military, Veterans, and Society Program

As evidenced by Christopher Nolan’s biopic, Oppenheimer, working with and doing research on nuclear energy requires a certain cache of skills and education. While today nuclear engineers are not tasked with discovering exactly how to harness nuclear fission, in the military context, these engineers do oversee critical projects that apply nuclear technology to weapons systems and power generation. However, the United States military is in the midst of a recruiting crisis, with the services struggling to fill their ranks and retain talent. As it currently stands, the military captures talent when servicemembers enter as either privates or lieutenants, and then this pool steadily decreases as servicemembers leave to pursue other careers. For roles that offer particularly competitive pay or benefits in the private sector, it can be difficult for the services to cajole their people into staying beyond their mandated term of service. One potential solution to this is increasing the use of lateral entry for specialized roles, such as nuclear engineers, within the military. Currently, this option exists for medical officers but is not significantly utilized for other sectors. Allowing mid-career professionals in critical fields to enter the military could alleviate some of the current stress on the system, as well as capitalize on expertise that can advance military research and capabilities.

LCDR Stewart Latwin, Senior Military Fellow, U.S. Navy

Since the Cold War, the understated backbone of great-power competition has been the threat of nuclear weapons. Nowhere is the backbone stronger than in the Navy’s submarine force. Ballistic-missile submarines represent one-third of the nuclear triad, perhaps the most important leg since their location is unknown to adversaries and therefore difficult, if not impossible, to eliminate. While the aircraft carrier is often seen as the face of the Navy’s presence, the boomer thrives in its deafening silence. Its location at any specific time may be hidden from the world, but its presence is felt by any who threaten American security.

The fact that the highest priority acquisition project for the Navy is the Columbia-class submarine shows how much value the Navy places on its nuclear deterrence capabilities for future conflicts. Although we hope to never use the weapons, the knowledge that we can launch them at any time and from any place remains the strongest deterrent against an attack against the United States and its allies. Whether providing a first-launch capability or retaliatory strike, the ballistic-missile submarine will continue to provide nuclear security far into the 21st century.

LCDR Stewart Latwin is the Navy Federal Executive Fellow at the Center for a New American Security. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy or the Department of Defense.

Valeria Allende, Executive Assistant

Oppenheimer will remind global viewers of the devastating consequences following the dual-use research of nuclear weapons and the desperate need for nonproliferation reform.

For decades, the debate surrounding policy for nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament has been vulnerable to great-power competition and regional instability, but the reality is that while large-scale nuclear war might seem distant, the rise in the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the materials to make them has continuously prevailed.

Nuclear-weapon states have not welcomed reform to existing nonproliferation policies. In fact, all nuclear-weapon states have refused to sign the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). The United States and critics of the TPNW argue that it contradicts the already existing Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), while supporters argue that it builds off the previous treaty and was created to help address one of the stagnant pillars of the NPT—disarmament. The TPNW is the first of its kind to bring forth a comprehensive ban to nuclear weapons. The United States and other nuclear-weapon states’ decision to boycott the TPNW is stifling nonproliferation and disarmament policies. Although the United States strongly favors the NPT, that treaty is not enough to rectify nuclear disarmament.

The argument is not for the United States to rid itself of its nuclear arson and become vulnerable to nuclear-weapon-owning adversaries, but rather to not vehemently oppose innovation for nuclear policies that have adapted to today’s security environment. Where it stands now, alarmingly, no nuclear-weapon state is offering significant counter solutions to the issue of nuclear proliferation and the daunting possibility of another nuclear arms race.

The Legacy of the Bomb

Bill Drexel, Associate Fellow, Technology and National Security Program

Amid escalating competition between superpowers on AI technologies, Oppenheimer’s life provides a valuable prism through which to consider scientists’ role in shaping the political dynamics of their creations. Initially, Oppenheimer and many other leading physicists had very strong inclinations toward robust multilateral solutions to nuclear dangers, a position no doubt shaped by the success of international scientific cooperation and one which is paralleled by many AI engineers today. But the hard political realities of the era derailed those aspirations, de-legitimated many physicists’ early attempts at advocacy, and considerably altered Oppenheimer’s own outlook on the potential to work together with the Soviets. Though this history would be tragically eclipsed by the Red Scare—with Oppenheimer as a preeminent victim—it is worthy of deep reflection in our current day as we consider how to approach the dangers of AI competition with China.

Michael Depp, Research Associate, AI Safety and Stability Project

Oppenheimer and the rest of the Manhattan Project birthed a new technology whose power they could calculate, but whose political ramifications they could never predict. This immense achievement of science and technology created a new political order its creators had no control over, and one that many, including most famously Oppenheimer himself, would come to regret. As scientists try to repeat these technological revolutions with artificial intelligence, we are even more in the dark about its political future. All we know is, just as nuclear weapons have become an indispensable part of national security, so too will AI.

Many look with hope to the success we have had in harnessing the atom as a model to copy for AI regulation and international control, but often underestimate the difficulty in repeating it. Control of nuclear weapons required clear analysis, hard work, diplomacy, and restraint at a time when few had access to the technology and the cost of a mistake was both clear and apocalyptic. This will be impossible to easily replicate in the face of a technology that is easier to produce and proliferate and whose risks are not clearly understood. Instead, we may have to prepare for a reality where AI is diffuse throughout the world and often used far differently than its creators would like. Oppenheimer may not have easy lessons that we can apply to the future, but seeing the arc of a life spent building something powerful and then being consumed by the political changes it unleashes may be the lesson itself.

Jocelyn Trainer, Research Assistant, Energy, Economics, and Security Program

When thinking of the conversation surrounding nuclear fallout and deterrence, popular cinema and literature seldom interweave gender discussions into nuclear security considerations and hypothetical apocalyptic scenarios. In 1987, Carol Cohn broke from this norm by writing that, “The history of the atomic bomb project itself is rife with overt images of competitive male sexuality, as is the discourse of the early nuclear physicists, strategists, and SAC commanders” in “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals.” Those assessing nuclear issues through a gender lens see that these words ring true to this day—or at least to 2018 when President Trump taunted North Korean leader Kim Jong Un with a Tweet that said: “I too have a Nuclear Button, but it is a much bigger & more powerful one than his, and my Button works!” One must wonder, in a world where Oppenheimer and Barbie crossover, could our collective security rest on more than a bomb measuring contest by world leaders on the global stage? Here’s to hoping for a modern discourse on nuclear security and nonproliferation!

Taren Sylvester, Research Assistant, Military, Veterans, and Society Program

Nuclear innovation was one of the most important scientific developments of the 20th century. It had significant impact on the civilian energy sector and fundamentally changed how states interacted strategically. While the development of nuclear technology highlighted the incredible achievements possible by investing in research, it also provides the most extreme example of the dangers of unfettered ambition. Echoes of this ambition can be felt today in the pursuit of many dual-use technologies that pose outsized risk to human life and livelihood. Be they advancements in synthetic biology allowing hostile actors to manipulate viral genetic material into superbugs or AI programs that can enhance cyber-attacks against critical infrastructure, dual-use research must be approached with the assumption that it will be taken to unknown extremes. The responsibility belongs to both the individual researcher and the funding institution. There is no holding back progress, but relying on good faith actions, societal norms, or human nature and reason to constrain the use of technology is to leave unclasped the lock on Pandora’s box.

Noah Greene, Project Assistant, AI Safety and Stability Project

In 1942, and the immediate period thereafter, the progenitors of the Manhattan Project were extremely concerned about the ability of state actors to rival the United States' nuclear arsenal. The subsequent result was significant attempts to prevent Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union from stealing nuclear secrets. The exposure of Soviet spies like David Greenglass and others reaffirmed the fears of American officials that one of the greatest threats to U.S. security was the rise of other nuclear powers. These 20th-century nuclear proliferation concerns have not dissipated and have been mixed with emerging technological risks. Nuclear weapons systems and their corresponding facilities are now vulnerable to cyber-attacks and AI-enabled systems may very well shift the strategic stability landscape. This reality is a far cry from what a world with nuclear weapons was initially conceived as.

As you watch Oppenheimer and read the corresponding historical narratives that have spawned its release, it is important to critically assess what our society got right and what it got wrong. Significant updates in the arsenals of nuclear-weapon states will continue to take place in the near term and, as a result, old questions will need to be answered again with new technology in mind. Under what conditions is extended deterrence through nuclear capabilities possible? What policies are needed both unilaterally and multilaterally to mitigate nuclear weapons proliferation? And just how bad would a nuclear exchange between states be? While Oppenheimer does not answer these questions, it will certainly keep the debate going across the world capitals.

Laredo Loyd, Intern, Technology and National Security Program

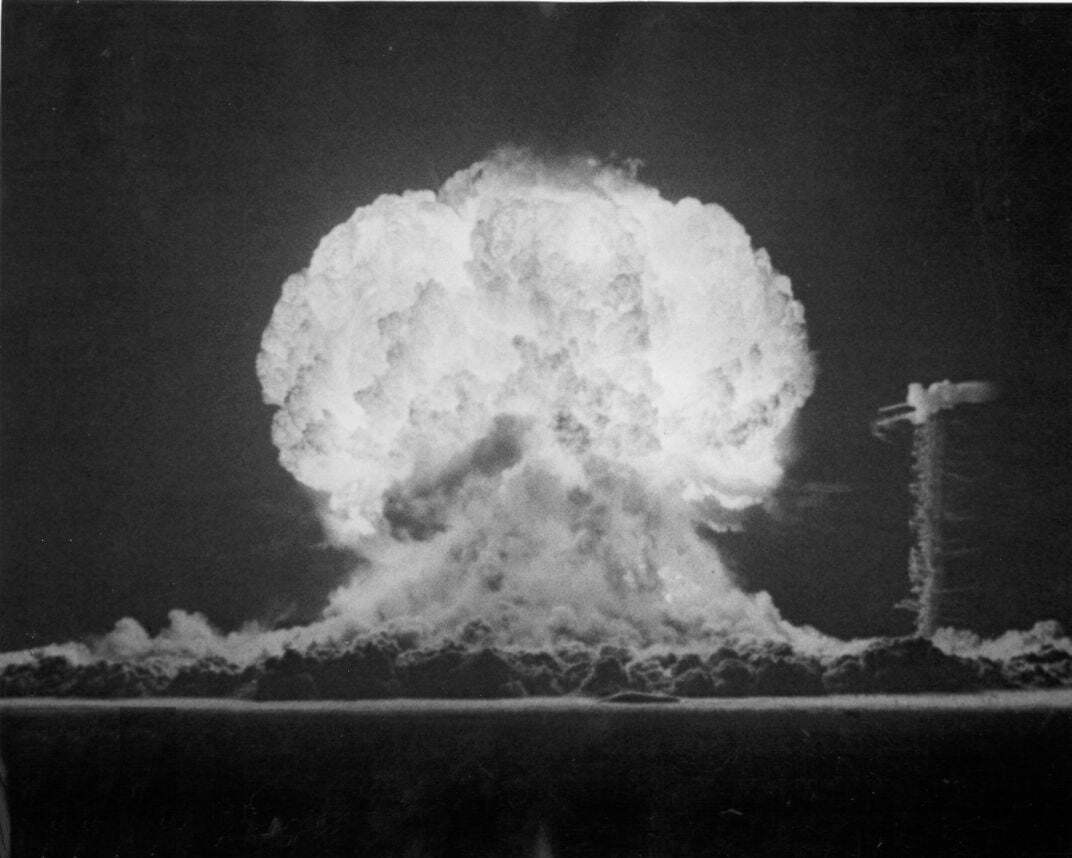

In 1914, H.G. Wells wrote The World Set Free, a sci-fi novel with the first written conception of atomic weaponry, published decades before physicists even had a working understanding of nuclear fission—splitting the atom. 31 years after the book, in 1945, Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project would reach fruition with the successful Trinity Test (spoiler). In just three decades, atomic weaponry went from science fiction to brutal reality. The rapid development of such a technology underpins what’s at stake in tech strategy today.

Two thoughts to bear in mind: First, though the project’s speed in execution was remarkable, it was by no means a singular endeavor. The theory and experiments necessary for this operation were done decades before, through collaboration among the world’s top physicists, and then achieved in the project with help from our allies—British, Canadian, and other scientists. Reaching the pinnacle of technological achievement requires leadership but is a collaborative endeavor, not one accomplished by going it alone. Second, Wells’ novel predicted a time after atomic wars, where the world changes its nuclear focus to pursue unlimited energy and lasting peace rather than weaponry. Atomic bombs were a fantasy in 1914, but it turns out that peace following their use was the actual fiction. This thought in particular would stay with Oppenheimer long after Los Alamos. Much of technology today, from AI to quantum to biotechnology, holds the same double-edged sword, offering both unlimited prosperity and catastrophic potential.

We can maintain leadership in technological development, but it won’t be possible without collaboration with our allies and partners. Similarly, these new technologies will likewise require a modernization of how we approach both responsible use and cooperation beyond current alliances. These principles are necessary for U.S. technology strategy; they've gone hand-in-hand for over a century, and Oppenheimer is a great reminder.

--

All CNAS experts are available for interviews. To arrange one, contact Alexa Whaley at awhaley@cnas.org.

Disarming the Bomb

Negotiations to return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), known commonly as the Iran nuclear deal, reached an impasse this past year. Further, Iran made parall...

Avoiding the Brink

The United States is entering an unprecedented multipolar nuclear era that is far more complex and challenging than that of the Cold War. This report examines potential trigge...

Atomic Strait: How China’s Nuclear Buildup Shapes Security Dynamics with Taiwan and the United States

This report examines the intersection of China’s nuclear modernization and cross-Strait tensions, especially how they might play out during a crisis, contingency, or conflict ...